Anthropology, as a discipline, thrives on critical thought and on questioning the assumptions that shape our understanding of the human experience. And yet, in attempting to define something as foundational as culture, the field seems trapped in a paradox: the more we try to pin it down, the more elusive it becomes. Sitting in class, staring at the words,

“Culture is the learned, shared knowledge that people use to generate behavior and interpret experience”

I was struck by a peculiar irony. Here was a concept central to anthropology, yet its definition was anything but settled. As the discussion unfolded, students attempted to refine or reinterpret the definition, only for another definition, given by a different professor, from a different textbook, to surface. This moment encapsulated a larger issue: Why are anthropologists so obsessed with defining culture? If the goal is to study people and their ways of life, does this fixation on defining an already fluid and evolving concept actually serve us, or does it create more obscurity than clarification?

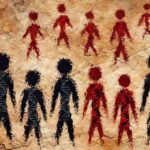

The exercise of breaking down the definition on the board only deepened my existential crisis. If culture is “learned,” does that mean every individual who acquires knowledge belongs to a culture? If it is “shared,” does that assume equal access to knowledge within a society, despite the existence of subcultures, countercultures, and elite institutions that control what knowledge is disseminated? The definition loops back on itself, forcing us to redefine learning, sharing, and behavior, concepts that, in turn, require their own debates. Even in applying the standard anthropological tool of ethnography or participant observation, we find ourselves describing cultural behaviors using the very word we seek to define. The attempt to categorize culture often leads to simplifications that fail to capture its dynamic, living nature. Culture is not a fixed entity but an evolving process, and yet, anthropologists continue to package it into definitions that imply boundaries. This becomes even more problematic when we recognize that the term “culture” itself has a history, a history tied to nationalism, exclusion, and the “us vs. them” mentality. From the German Kultur, once used to define a people and their land, to its use in modern political rhetoric, the term has carried implications far beyond its academic intentions. So, how far can we break down a concept before it dissolves? Perhaps the real question isn’t what culture is, but whether defining it at all is a productive exercise. If definitions are meant to bring clarity, why does defining culture seem to only make it more obscure?