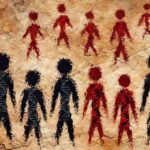

Before we had 3D scanners, we had pencils. Some of the earliest anthropologists were also artists, carefully sketching bones and bodies with attention to proportion and morphology. These hand-drawn illustrations weren’t just beautiful, they were foundational. For decades, they were how we shared discoveries, tracked comparisons, and taught each other across continents.

Then came calipers. Measurements made everything feel more precise. Ratios, indices, and formulas brought a new kind of scientific rigor to skeletal analysis. This was the rise of what shall be called metric anthropology, a language of numbers used to interpret form, function, and identity.

The next leap came with photography and radiography. These tools gave us documentation with minimal interpretation. Unlike a sketch, a photograph could be “objective”, though of course, what we choose to capture (and how) still reflects bias today. Still, X-rays, CT scans, and macro photography gave us new ways to see inside, to preserve, and to diagnose.

Now we live in the era of 3D where my specialty lies. Structured light scanners, laser scanning, and photogrammetry have changed the game entirely. We can digitize an entire skeleton in high resolution, preserve it indefinitely, and share it globally, all without physical transport or risk to the remains. Even more, we can layer in data such as annotations, color mapping, texture references, and more which have proven to be extremely effective.

What’s consistent across all these eras is the desire to preserve and communicate. To translate what we see into something others can understand. From hand sketches to high-tech renderings, the story of documenting human remains is also a story about trust, interpretation, and evolving definitions of “accuracy.”

As we move forward, the question isn’t whether we’ll keep adopting new tech which it is certain we will. It’s how we continue to think critically about what tech allows us to do, and what it might obscure in the process.